An interview with David Hine

A comic-book writer best known for Bulletproof Coffin (Image) and Silent War (Marvel)

First published 22 December 2019.

This week I’ve interviewed critically-acclaimed comics writer David Hine, whose new Image Comics trade paperback collecting the first story arc of his series Sonata with Brian Haberlin is out this week. One of the things that I love most about David and his body of work is his fierce independence, in a career that has seen him work for all the top US comic publishers, on characters including Green Lantern, and Daredevil, alongside a raft of stories, characters and concepts that he’s created.

There’s something inspirational about the man who co-created Spider-Man Noir for Marvel in 2009 (seen most recently in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse!) carving out a career based on his own creations, in an industry that’s heavily weighted towards writing licensed stories and giving up the rights to everything you create. His Image Comics series with Doug Braithwaite, Storm Dogs, was ahead of its time in almost every respect and is something that I feel modern readers would enthusiastically embrace. I also recently finished reading his new Soaring Penguin Press graphic novel, The Bad Bad Place, with Mark Stafford, which is a deeply unsettling Lovecraft-esque tale of “urban unease” that’s beautifully British and very disturbing!

1/ What accomplishment in your career to date are you most proud of?

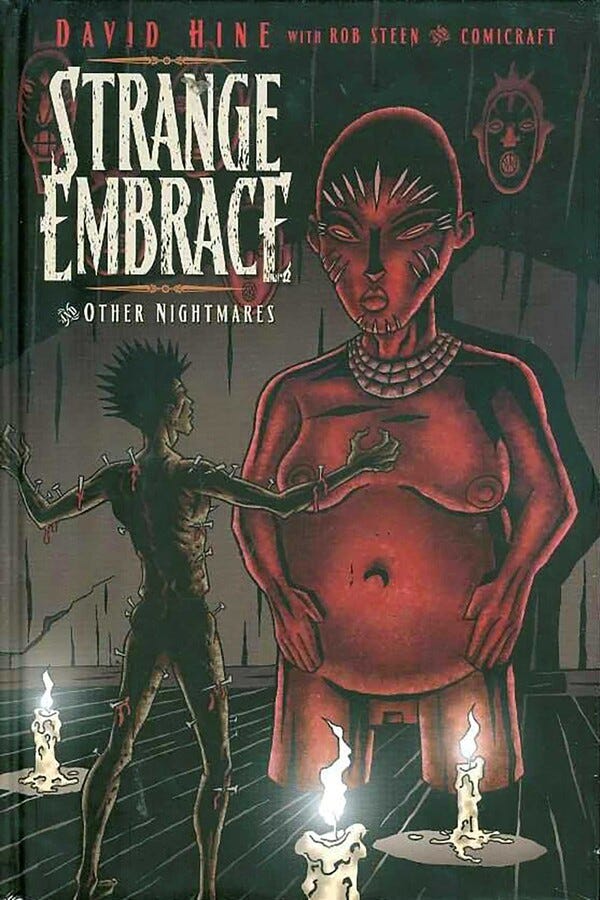

I think that still has to be my graphic novel Strange Embrace, which was first published back in 1993. This was the first time I undertook a full graphic novel, writing and drawing without a confirmed publisher when I began it. I had my ideas of how non-mainstream comics could be done, based on what I was seeing coming out of Europe, specifically the work of Munoz and Sampayo (Joe’s Bar for instance) and the novelistic work of Tardi, working with various prose writes like Léo Malet.

Strange Embrace was the result. There were no editors and no deadlines and best of all, I had enough savings at the time to spend a year working on it without the distraction of having to do other paying jobs. I look back on that period with great fondness because I was able to totally immerse myself in a single piece of work and I think it shows.

2/ What or who inspired you to begin your journey as an artist, and if different, what inspires you now to keep creating?

I’m going to take the term ‘artist’ as including the art of writing. As far back as I can remember I would immerse myself in fictional worlds, whatever the medium. I was drawn to fantasy and science-fiction more than anything. The Narnia books, The Trigan Empire in Ranger and then in Look & Learn, Dr Who on TV along with Lost in Space, Star Trek, The Time Tunnel and all those other great American TV shows. I read masses of science-fiction. Favourite authors included Ray Bradbury, Brian Aldiss, Michael Moorcock, Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison.

“The ability to cut dialogue to the bone is a major skill you need to acquire if you are going to write for monthly comics.” – David Hine

I knew by the time I was eight years old that I wanted to write and I have loads of notebooks filled with two completed novels, short stories and innumerable incomplete novels that would peter out after a couple of chapters. One of those completed novels was a western, so I wasn’t totally fixated on science-fiction. When I stumbled on imported Marvel and DC comics in the newsagents at about the age of 10, I became obsessed with the medium and that’s when I started to focus on drawing so I could emulate the creators I admired, like Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby and later Steranko, Wrightson, Neal Adams and later still, the underground artists like Vaugn Bodé, Robert Crumb, Greg Irons et al. I won the school prize for art for ‘O’ level and school prize for English at ‘A’ level so I guess that shows my determination. Sadly, I’ve never won any prizes for anything since.

When I started out, it was the old masters of the medium who inspired me, then the mavericks, and now it’s the younger creators who are entering the comics medium. Some of them are my Graphic Storytelling students from the Animation Workshop at VIA University in Denmark. They all inspire me with the freshness of their outlook and diversity of styles and their outstanding talent. Some of them are starting to publish their work now. Emil Friis Ernst just published his first graphic novel, Dr Murder and Emei Burell contributed to Soaring Penguin’s anthology, Meanwhile, and then published a biography of her mother, which was recently picked up by BOOM! Studios.

There is a whole pack of new young creators snapping at the heels of us old guys. Luke Healy is another artist who impresses me. I’m amazed at his output – and he’s still in his twenties. So, yeah, the youngsters with their wide-eyed enthusiasm and anyone who pushes the boundaries, like Richard McGuire with Here or anything by Chris Ware.

3/ Can you give me a snapshot of your creative process from start to finish – do the nightmares that you write come from immersing yourself in misery or do you write about bad, bad places while sipping smoothies in the sun?

It’s a long process from the germ of an idea to finished comic book. Immersing myself in misery is definitely part of the process though I have also written far too much on holiday – not so much sipping smoothies in the sun, as labouring in a hotel room while my partner was soaking up the sun on the beach. Not recommended, though it is a good test of the strength of our relationship.

I have two distinct kinds of work. There’s the mainstream work, which is more commercial and almost always work-for-hire. That may be working with existing characters, from Batman, or Spider-Man to Spawn or Will Eisner’s The Spirit. The challenge there is to come up with original ideas that still keep the integrity of popular characters that many others have worked on before. Editors will usually give me some idea of theme, or the direction they want a book to go in. I’ll come up with a story pitch, which is couple of pages long. If that’s approved I move on to breaking the story down into 20-page chapters, usually running to about 100 – 120 pages total. That part of the process is all about pacing, keeping the interest of the reader and building the drama, taking the characters through a journey that tests them and pushes them into new areas. The trick with a character like the Batman is to develop the character without changing the essence. Give the readers something new without betraying what the character stands for.

Once the chapter outlines are approved I start breaking it down into pages and then panels. That’s all about the beats, panels are minor beats, pages are major beats. I try to make every episode complete in itself, as far as possible, with some kind of hook or cliffhanger to make the next episode unmissable.

I sketch out thumbnails of each page so I can see what I need to achieve dramatically. That means choosing establishing shots, mid-shots, close-ups etc. I’ll then write dialogue, then cut enough of the dialogue so I don’t go over 150 words to the page. The ability to cut dialogue to the bone is a major skill you need to acquire if you are going to write for monthly comics. 20 pages with 150 words or less to the page is not a lot to develop plot character and theme.

The last part of the job is the bit I enjoy the least. This is the full panel description, where you make sure the artist doesn’t miss out on any element of storytelling. That will include establishing props that you are going to need five or ten pages later. You don’t want that matter transmitter or raygun or package of cocaine to just appear out of nowhere (unless it’s the matter transmitter doing it). It can become mind-numbing when, for instance, you realize on page 15 of episode three that your character has to climb out of a window that was drawn with iron bars on it in episode two. It’s the detail that makes a comic convincing but it can drive you crazy. I’m always happier doing this part of the job when I know the artist well and can write the script in a more conversational way. My most frequent partners in crime have been Shaky Kane and Mark Stafford and we pretty much share the same headspace when we’re collaborating.

After the script is done and sent, you wait for the art to come in, at which point you feel ecstatically joyful or sink into a mire of depression. Happily, it’s more often the former.

The location for work is important for me too. I like to change it up as much as possible, so though I do have a studio set up for work with reference books, piles of notebooks and my trusty laptop, I also like to work in cafés, hotel rooms, on trains and planes or waiting in airports. Sitting in the garden in summer is also good.

The process for creator-owned work is similar in some ways to work-for-hire. You still have to pitch to a publisher, but you will be left to your own devices once the project is greenlit. The whole thing is a lot more enjoyable because the straitjacket of working with characters that are described as ‘properties’ is gone. I feel totally liberated working on things like The Bulletproof Coffin or Lip Hook and The Bad Bad Place. I am eternally grateful to publishers like Eric Stephenson at Image, Emma Hayley at SelfMadeHero and John Anderson at Soaring Penguin, who had enough faith in me and my collaborators to allow us to pursue our twisted visions.

That was a little more than a snapshot, wasn’t it?

4/ If you woke tomorrow and were no longer constrained by time, budget or even skills you haven’t learned yet, what would you make?

It’s nice that you think I’m still capable of learning new skills. I have a couple of ideas for graphic novels that I would love to do as complete projects, making the art, colouring, lettering, the whole shebang. However, my drawing skills never have, and never will reach the point where I can recreate what I see in my head. I lack the mind-to-hand motor skills. I also lack the digital skills for the more fantastical imagery. The only artist who has come close to making images that I need for one of those projects is Frazer Irving. Ideally I would have the ability to inhabit his head for a year or so to make the artwork.

More realistically there’s a prose novel or two I want to write and then I hope to make more comics with Shaky Kane and Mark Stafford. Mark and I already have a plan… it just requires the time and a wealthy benefactor. If I woke up to the magical world you suggested I would probably go for the graphic novel project with Mark first, then lure Shaky back for another series of monthly comics in the style of The Bulletproof Coffin (but different), then my personal book project, which I am not even going to attempt to describe, with illustrations by me using the magically acquired skills of Frazer Irving.