An interview with John Harris Dunning

+ a review of comedy folk-horror Get Away, which I urge you not to watch 🚫

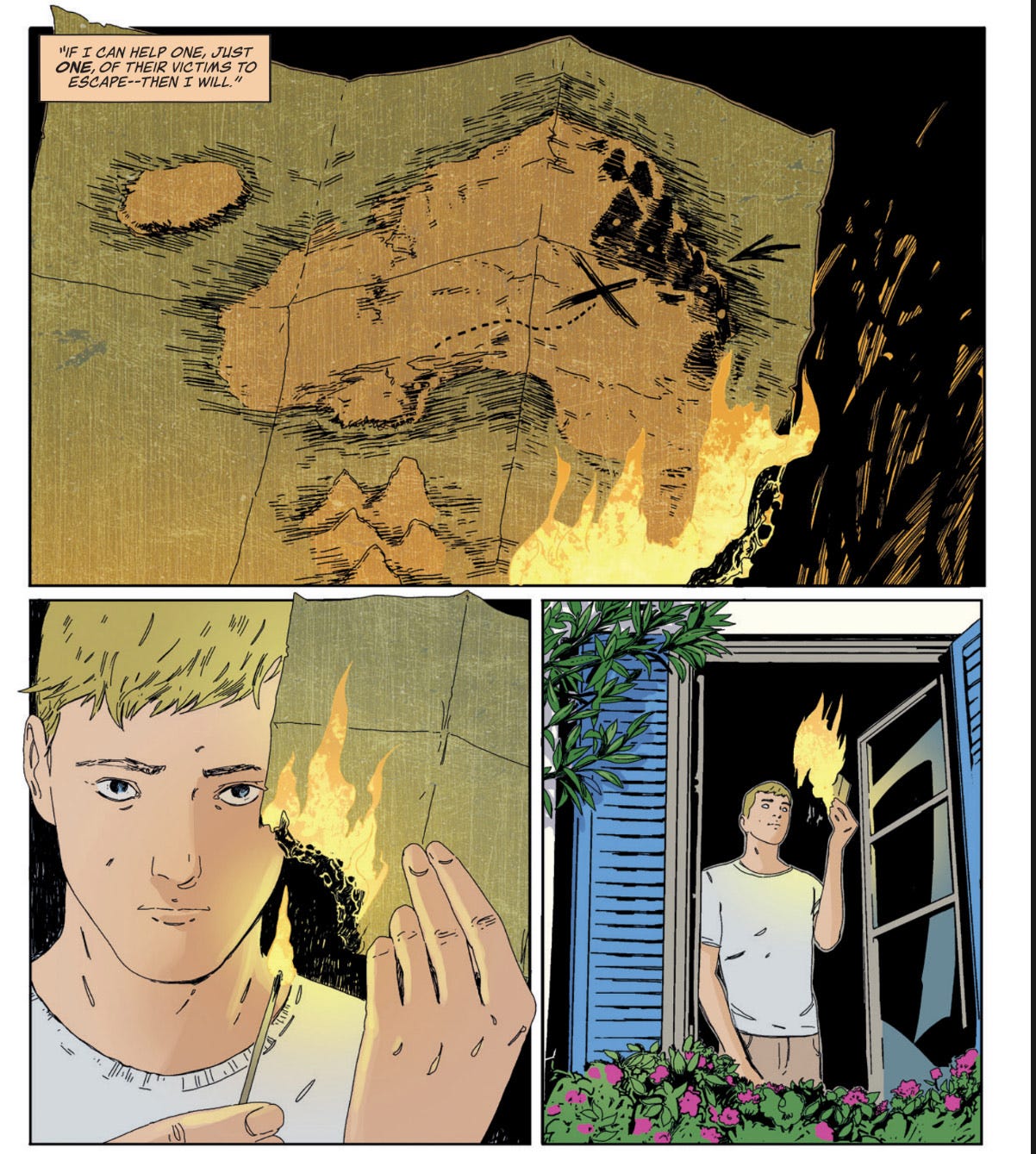

Today in IF YOU GO AWAY I’m interviewing writer John Harris Dunning, whose comic-book series Summer Shadows (with Ricardo Cabral) and Ripperland (with Steve Orlando and Alessandro Oliveri) are both currently being published by Dark Horse Comics.

Beneath that interview, you can read my review of new comedy folk-horror Get Away, an artless film that feels like it was made completely without love.

As a journalist writer John Harris Dunning has contributed to The Guardian, Metro, GQ, Esquire, Dazed and iD. In 2014 he instigated and co-curated the Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK exhibition at the British Library, the largest and most prestigious exhibition of comics in the UK to date.

I can’t remember when I met John, or how, other than through our shared networks in the UK comic-book industry. What I can say is that it feels like I’ve known him forever, despite knowing very few details about his personal life, and that the way he treats other artists with respect and compassion puts me at ease in his company. When I was regularly attending comic conventions in the UK I always enjoyed our conversations, late at night in the bar, planning our next steps and commiserating over how difficult it could be to get anything made. Seeing the recent success of his two new Dark Horse series, I suspect that we’ll be seeing a lot more of John in the years ahead.

Can you tell me a little about your journey as a writer?

I started writing comics as a child. I grew up in South Africa where there were no comic book shops, so it was just whatever you found on the spinner rack or in the book exchange where you could swap comics by amount of comics as opposed to by value. I loved the female characters most, like Wonder Woman, Batgirl, Dazzler and She-Hulk, as well as the anthology horror comics like Ghost Manor. Then as a teenager, along came 2000 AD and it blew my mind. This was back in the day when the likes of Alan Moore, Grant Morrison and Simon Bisley were contributors.

I studied film, and when I arrived in London I started writing for magazines like Dazed & Confused, Esquire, GQ and iD, and papers like The Guardian and the FT. I was mostly interviewing film directors and actors; I studied film back in Africa. My first comics were self-published - I collaborated on a project called Lolajean Riddle with Sacha Mardou, whose book Past Tense is blazing a trail at the moment. Check it out. I'm so proud of her! That led on to publishers getting interested. It was a slow burn getting published, but I've always been a voracious reader of comics.

Of the projects that you've published to date, is there any one that you'd say best articulates your creative voice?

I suppose to date that's Summer Shadows, for two reasons. One, because it's my most recent, so it's most aligned with where I'm at right now. Two, I wrote it solo. My new series Ripperland was co-written with Steve Orlando (Scarlet Witch, Midnighter), which was a fantastic experience, but as a collaboration by its very nature it needs to be more of a blending of visions. It was exciting in its own way, to see where it went. I'm really pleased with how it came out and I'm as proud of it as I am of any of my solo work.

What is it that motivates you to write and have your motivations and inspirations changed over time?

Writer Anais Nin (A Spy in the House of Love) said, "Why one writes is a question I can answer easily, having so often asked it of myself. I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me — the world of my parents, the world of war, the world of politics." As always, I agree with Anais. It's a need I've always had. I do it to make the world bearable. I think the change is that as I get older, I realise that far from being a selfish act, it's a hugely generous one.

It can be really hard to fight for the space and time to create work, and creators are very seldom compensated for that. It's not so much about having one's say as it is about transmitting what one's learned for the benefit of others. I always felt a responsibility to write. The work of my favourite writers like William Burroughs, Anais Nin, Gayl Jones, Poppy Z. Brite, Chester Himes, Frank Herbert, JRR Tolkein, Alan Moore, Daniel Clowes and Grant Morrison have had such a huge impact on me and how I've lived my life - I feel the least I can do is to try to give something back by creating my own.

Can you name a piece of art that has particularly inspired your creative development?

William Burroughs and Anais Nin both had a profound impact on me when I read them at 18. They really exploded my world view and gave me permission to live in whatever way I chose. The specific works were Cities of the Red Night by Burroughs and A Spy in the House of Love by Nin. I also love Queer by Burroughs, and the current film adaptation is spot on - go see it! Comics writers like Ålan Moore with Swamp Thing, Grant Morrison with Zenith and Daniel Clowes with Ghost World made me realise I could write anything I wanted in the comics medium; they collapsed the division between high and low art for me.

Can you give me an overview of your two new comic-book series, not only in terms of plot but what they represent to you?

Summer Shadows is a supernatural psychological thriller. My inspirations for it were mostly cinematic: The Talented Mr. Ripley, Klute, Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby, The Ring and Dark Water (Japanese version). In horror, I like the idea of introducing something uncanny and then really dialling it up. At the heart of Summer Shadows is a gay love story. The gay experience is one of fear, initially at least, and a lot of queer creators are drawn to the horror genre as a result. Think James Tynion IV and Glive Barker, for instance. I wanted the story to be scary as well as poetic.

Ripperland is also a horror story, but it's more of a political satire. On the surface it's a police procedural, with an American and British detective playing off each other. That gave me and co-writer Steve Orlando the chance to really explore cultural cliches and expectations. I've never co-written a comic, and I was concerned about how it would work. I shouldn't have been. It was like going from being a solo singer to being in a band. That camaraderie was a blast. I'm sure that's not always the case, but we lucked out with our team-up. It was great working so closely with a writer as experienced as Steve and seeing his process. What a talented guy.

If you could create anything at all and budget and audience weren't constraining factors, what would you create and why?

The beauty about comics has always been that they aren't expensive to produce, and no one is in it to earn money (although that would be great!), so I don't think money would dramatically change my choices. I've come up through an indie route and thus far have only worked on self-generated projects I really believe in, so finding an audience hasn't really been a consideration. So, weirdly, I think whatever I create next is what I'd be creating, whatever the budget.

If I did have a huge amount of money, I'd set up some kind of arts grant for UK and American comics creators to help them free up the time to produce work. All the creators I know have had to make huge sacrifices to create comics, and it's sometimes painful to see, especially when you look at the rest of Europe and see how much their governments value and support their artists. Artists are the souls of nations and deserve support.

Review - Get Away (2024)

Last Saturday I watched comedy folk-horror Get Away. Launched on Shudder in the US at the start of December 2024, the film was unceremoniously dumped as a Sky Original Film on Sky Cinema/Now TV in the UK, never a sign of high quality, but I enjoyed the trailers and am a fan of the stars, so I hoped to enjoy it. At only 86 minutes long, most of the first hour felt flat and I waited patiently for the third act, confident that it would improve. When the bloodshed began, I laughed in all the right places, but after the credits had rolled and I reflected on what we’d watched, disappointment and something akin to anger were my overriding emotions. Get Away feels like a cynical film with nothing to say, made without love by a talented group of artists who deserved a better return for time invested.

Ordinarily I’d balk at wasting my time writing a negative review or spoiling the plot of a film that was so recently released, but in this case the end result was so maddening that I feel duty bound to try to understand what went so wrong. Ostensibly Get Away is the story of a British family’s much needed holiday to a remote Swedish island, where they intend to relax, unwind and watch the kind of private, local performance that anybody who has seen Wicker Man or Midsommar will be familiar with. In stronger hands you might call it a satire of folk-horror cinema.

The film stars and was written by Nick Frost, a brilliant talent best known for his starring roles in the sitcom Spaced and in Shaun of the Dead. Co-starring with Frost is Irish comedian, actor and screenwriter Aisling Bea (replacing Lena Headey at the last minute), wasted in a paper-thin role that gives her almost nothing to do.

The waste of Bea, one of the funniest actors of her generation, is nothing short of criminal. Her comedy-drama This Way Up (2019), which she wrote and starred in (alongside Sharon Horgan), forms part of a recent trinity of incredible British television series that also compromises the more famous Fleabag (2016), written by and starring Phoebe Waller-Bridge, and Back to Life (2019), written by and starring Daisy Haggard. Each of these series creates a platform for a brilliant writer-actor to explore ideas in comedy that most creative teams would be afraid to touch, and as vehicles to show their range and potential as actors in a way that previous projects had not (much like Bill Hader in Barry). Fleabag might be the one that made the biggest international headlines, but for my money This Way Up was the most entertaining of the three.

The problem with Get Away, in which the first two acts feel flat and demonstrate little in the way of character development, becomes apparent in the third act, which subverts everything that came before in an absolute bloodbath. I can’t believe that I’m typing those words as a criticism. You know that it’s leading towards something and you want it to hurry up and get there. Then when it comes, there’s a whirlwind of sound and fury that feels fun until it ends and you realise that nothing of consequence happened, you didn’t care about a single character, there wasn’t a moment on screen that hadn’t been done better in another film or television series, and then it was over.

I love horror. Everything from ghost stories and haunted houses to maligned “torture porn” and video nasties. They all have their place. Apart from, it seems, Get Away. The problem is that the subversion that Get Away offers has been done before, much better, by artists who had something to say. Michael Hanake’s Funny Games (1997) and even his own American remake (2007) subverts the audience’s desire to see violence on screen, making us complicit as viewers in the carnage and torture. When we watch Funny Games, we see our darkest desires reflected on the screen, alongside innovation, humour and nihilism.

Rob Zombie’s Devils Rejects (2005) takes the template from gritty exploitation films and shows us what it would really be to root for a family of anti-heroes, to the extent that we’re taught to empathise and identify with a group of absolute sadists, while enjoying Zombie’s tribute to the actors and cinematic milestones that paved the way for his film. It isn’t for everyone, but Zombie’s more-is-more approach eschews irony and goes for the throat in a way that few other directors can manage.

Recent record-breakers like the Terrifier (2016) series make a virtue out of gore, playing a tasteless game of one-upmanship with every slasher and horror series that came before and contributing to a tradition that every gorehound and extreme horror fan can recognise. Director Damien Leone, with every scene, says to the viewer, you thought that was bad? Wait until you see this. The nature of these gore films is that they inevitably pale into insignificance eventually, as the next film comes along and eclipses what came before, but this is the nature of extreme outsider art.

Get Away offers none of the above. Unfathomable gallons of gore fill the third act, in a film that tonally seems to think that it has more in common with a traditional British sitcom than it does anarchic horror. The disconnect between the nastiness of the violence and the glib tweeness of the jokes demonstrates a complete lack of self-awareness. All that the body count in Get Away does is desensitise the viewer, to no effect, ensuring that the next horror comedy will need to match these levels of blood to get a rise from even the tamest of audiences. The filmmakers treat extreme gore like a jaunt that you’d see on a cheeky Saturday night variety show, without doing anything to earn it.

Worse, everything that Get Away seems to want to do was done exponentially better in Ben Wheatley, Alice Lowe and Steve Oram’s Sightseers (2012). Funny, grounded, tragic and knowingly unsettling in a way that Get Away is not and can never be, I would recommend Sightseers a hundred times before a first watch of Get Away. Get Away contributes nothing to the horror or comedy genres, unsuccessfully tries to satirise films that are infinitely more interesting, and wastes the comedic talent of actors who should have been encouraged and allowed to do more work on the script and decide what they wanted to achieve with the story before the cameras started rolling.

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025)

The world is a little smaller without David Lynch in it. An artist and genius who was unafraid to acknowledge the complexities of the universe, fusing beauty, darkness and honesty in all that he created. Sex, violence, love and hate collided in his works, coming closer to capturing the full spectrum of emotion and human experience than almost any of his peers.

From a personal perspective, Lost Highway (1997) taught me how to engage with a work of art on multiple levels, how to appreciate ambiguity and duality, how to think about different perspectives, about symbolism, about the alchemy involved when so many disparate elements combine to create something that amounts to more than the sum of its parts. David Lynch gave the world a lot of gifts, but Lost Highway felt like a film that was made just for me.

You might also enjoy

An interview with Steve Orlando

An interview with Steve Orlando, co-writer of Ripperland with John Harris Dunning. Originally published 29 March 2020.

HERETICS

Set in 1999, HERETICS is a folk-horror story following the journey of investigative journalist Isobel Lockwood as she travels to a remote island off the coast of Scotland in an attempt to save her younger sister from the Children of the Sun, the free love cult founded by their father, which Isobel escaped from ten years earlier.