🍂 Horror season & Withered Hill 🎃

David Barnett interview + Scare City + Mysteries of the Unknown + the Cornish Gothic

October is upon us and we have finally entered Halloween season, my favourite time of year. For IF YOU GO AWAY this time I’ve interviewed author David Barnett about the release of his new folk-horror novel Withered Hill, revisited my favourite childhood book, was chased through nightmares at Scare City, and attended the Dark Tourism Symposium at Bodmin Jail.

Horror has unequivocally been my passion for as long as I can remember, from an early obsession with drawing skulls on everything to the time that my primary school teacher made me sit alone to rewrite my final essay before being allowed to progress to the next year group, because she’d found the short story that I had originally written so depressing and horrible that she refused to mark it.

There’s something about our collective fear of the dark that fascinates and enthuses me. When I meet new people, I sometimes explain that I have a naturally sunny disposition and so to counter it I’m drawn to the most harrowing and horrific forms of entertainment.

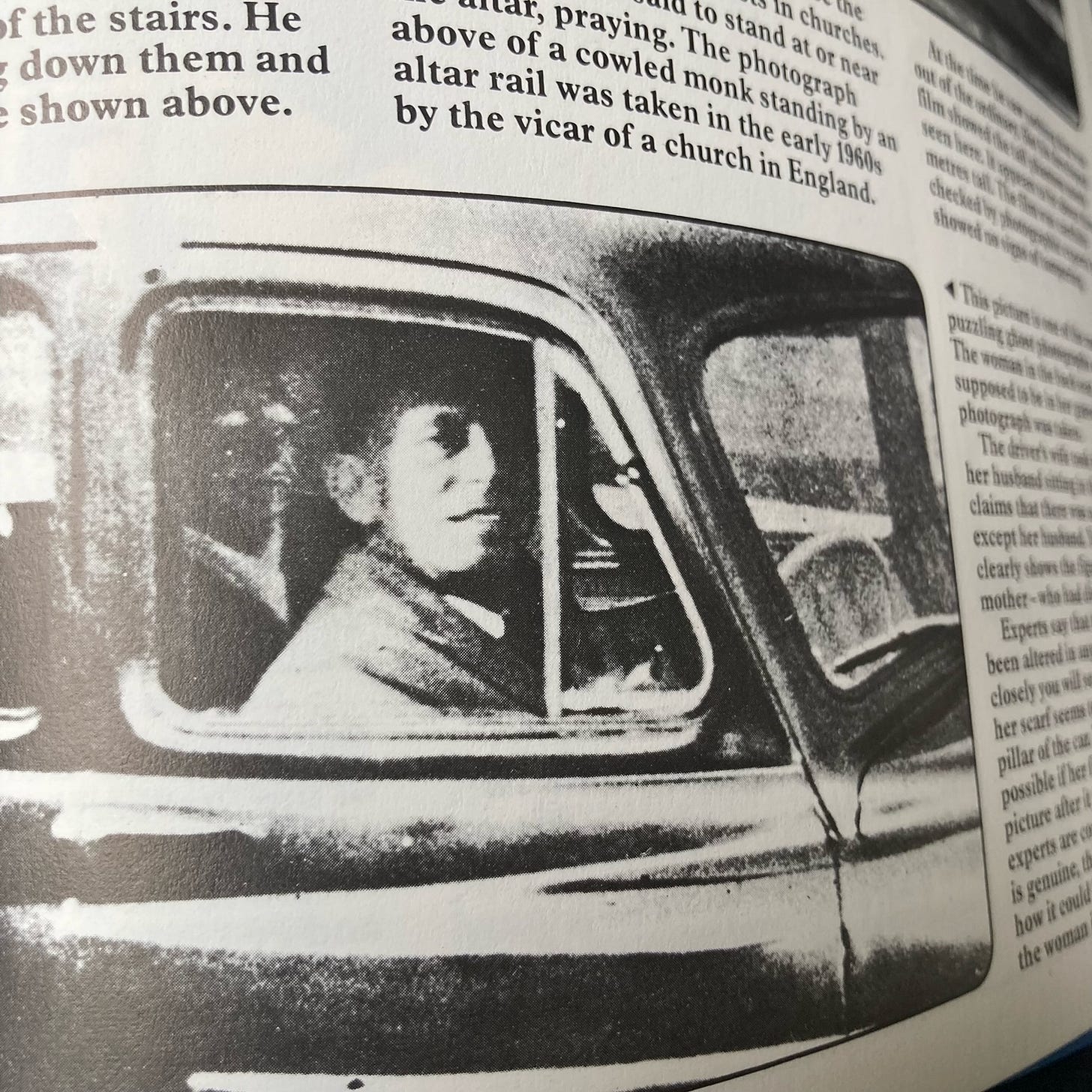

As a child, my favourite book was Mysteries of the Unknown. I didn’t know it at the time, but it collated three Usborne books that were published in the 1970s about Ghosts, UFOs and Monsters, under the label The World of the Unknown. I read that book so many times that the pages fell out, committing the grisly illustrations to memory while I learned about poltergeists, alien abductions and the Loch Ness Monster.

In 2019, Ashley Thorpe (the creative mind behind the film Borley Rectory, who I interviewed for IF YOU GO AWAY in September) and actor Reece Shearsmith supported a campaign with Anna Howorth, Usborne Director of Global Branding & UK Marketing, to bring the original World of the Unknown books back into print. Ironically, I remember the campaign and was broadly supportive at the time, but it wasn’t until this week when I saw the cover to Mysteries of the Unknown that I realised that they’d been petitioning for the return of the children’s books that propelled me towards a lifetime of writing horror.

Writing about Mysteries of the Unknown has made me yearn to read the book again so I’ve ordered a second-hand copy. I can’t wait to revisit the stories that kept me awake in terror for so many nights.

Last week I visited Scare City in Chorley, North West England, a massive outdoor scare attraction on the site of the abandoned Camelot Theme Park. I went with my nephew on my wife’s side of the family. He was a cheeky pint-sized scamp when I first met him. Now he’s a grown man who Scousers fell over themselves drunkenly to fawn over in the scare mazes. Growing older is weird.

I’ve written about Scare City for Spooky Isles, “the UK and Ireland’s leading independent horror and paranormal online magazine”. I love visiting horror attractions and feel the compulsion to write about everything I enjoy, so plan to document my adventures more regularly.

Scare City: Horror haunts Camelot Theme Park: https://www.spookyisles.com/scare-city-camelot-chorley/

Scare City comprises the only set of scare mazes that I’ve visited where we were allowed to film and take photos throughout the experience. On reflection, I hated that part of it. The exorcism performance was overshadowed by a large group vying for the best place to film, phones glowing in the dark, and didn’t really bring out the chill factor, though phones were less intrusive in the more brightly lit zones.

Some of the scare zones in Scare City were incredible, particularly the post-apocalyptic junkyard filled with sparks and cannibal mutants, but I feel like the experience would have been more immersive if there’d been more storytelling before you entered each zone. The set designs, costumes and performances were excellent, but there was little in the way of introduction to most of the mazes. Even a signboard before each area that used the maze descriptions from the website would have helped to set the scene.

If you’re more interested in seeing my smiling face than reading about the experience, I created a Scare City reel on Instagram:

Look closely and you might spot the zombie on a chain that managed to kick a huge glob of mud in my eye, which I winked away and carried home with me, to emerge hours later.

This year I’m making more of an effort to support and write about the kind of events and public art events that I want to attend. Living in the far South West of England, you find that the rich London crowd arrive to take over the beaches and occupy second homes in communities that become ghost towns outside of tourist season, making it difficult for events and attractions outside of the summer to reach critical mass. This is not helped by having the most depressing public transport system that I’ve ever encountered and a single vital train line to London that closes regularly when high sea levels crash over the tracks.

Last week I attended the Dark Tourism Symposium at Bodmin Jail, held in collaboration with Falmouth University, as part of work to support the tourism and creative sector across Cornwall. The idea was to bring together speakers who could inform a debate about “the role of storytelling in tourism and business as well as in building social and cultural capital across the county, presenting ideas harnessing offseason tourists and giving an insight into the types of dark stories and places that exist in Cornwall.”

In practice, this looked like a series of talks from academics with a professional interest in Cornwall, Gothic fiction, ghost stories and the areas where they intersect. The star of the night was definitely Joan Passey, an academic from the University of Bristol who specialises in research around Victorian literature, nineteenth-century Cornwall and representations of the coast in literature and culture.

In a talk that was informed by her first monograph, Cornish Gothic 1830-1913, Passey spoke about the rich vein of evidence that her research uncovered to evidence the strong tradition of the Cornish Gothic in Victorian literature, covering authors that include Bram Stoker, Thomas Hardy, Wilkie Collins, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon.

Discussing the ways that place and geography lends the Gothic a particular flavour, Passey argued convincingly and fascinatingly for the particular influences of isolation, coastal communities, mining and shipwrecks on the creation of the Cornish Gothic, an otherworldly place where the past always returns.

Relocating to this part of the country almost a decade ago, I was drawn in part by the weirdness of Cornwall, a place associated with fairies, witchcraft and magic, but I didn’t know how long those connotations had been associated with the county. Passey referenced numerous travel guides from the mid 1800s that talked about Cornwall as a wild place, the last outpost of magic in England, due in part to the fact that it was the last county to be connected to the rail network that connected the rest of the county.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash, on the border between Plymouth in Devon, and Cornwall, was completed in 1859, unlocking the possibility of train travel between far Penzance and the rest of England, leading to an influx of tourism to this final outpost of myth and magic.

I could have listened to Joan Passey speak all night, but the thing she said that haunted me was that Samuel Taylor Coleridge was invited to visit Cornwall in the same year that he instead accepted an invitation by Wordsworth the visit the Lake District. Wordsworth and Coleridge’s poetry was essential in defining the Romantic movement, but imagine if Coleridge had travelled instead to a far-flung region of the supernatural and embraced his dark side, completing the fragments that tantalise us even now and escaping the condescending shadow of Wordsworth once and for all.

Other speakers at the Dark Tourism Symposium included Professor Ruth Heholt’s discussing everyday ghosts, Dr E Jay Gilbert talking about the afterlives of ghost stories, Dr David Devanny on avoiding regurgitating Cornish stereotypes when using generative AI, and Dr Donna Poade explaining her views on the ethics of dark tourism in the region.

The Dark Tourism Symposium was an interesting night, but nothing that came afterwards could match Passey’s anecdotes about my favourite Romantic poets or her impassioned and persuasive plea to acknowledge the importance of Cornwall to Edgar Allen Poe’s Ligeia. Once you start talking to me about Coleridge, everything else pales in comparison.

It must have been 2017 when I first met author David Barnett. I collaborated multiple times with artist Martin Simmonds between 2012 and 2016, culminating in our work together on the 44FLOOD series HERETICS. After logistics made completing HERETICS together impossible, Martin went on to work on the series Death Sentence: London and then the IDW/Shelly Bond series Punks Not Dead, with David Barnett. I wanted to resent the new writer who got to collaborate with Martin, but unfortunately David was too much of a nice guy, so we’ve kept in touch since.

An English author and journalist, Barnett’s increasingly successful career as a novelist includes Calling Mr Tom and There Is A Light That Never Goes Out, but he’s also written for the Guardian, Independent, Telegraph and BBC, as well as working on comics for DC’s Sandman Universe, 2000AD and Archie comics. I caught up with David to find out about his new folk-horror novel, Withered Hill, and tried to discover how his success straddles so many different genres and media.

1/ You have an eclectic range of published stories to your name – can you tell me a little about why that is and what attracts you to tell stories in so many different styles and genres?

The perception is that writers should usually “stay in their lane” and write pretty much the same sort of thing all the time. To be honest, this is really a business decision — if an author writes a book and it sells well, their publisher will want more of the same, because people who enjoyed the first book are likely to buy it. But most writers have wide-ranging tastes and interests, just like everyone else. I suppose I'm lucky that I've had the opportunity to write in different genres. I started off doing fantasy and steampunk, then moved into commercial fiction and rom-coms, and now added horror to the list. I am fortunate that I can do that. And, to me, a story is a story is a story. The genre isn't necessarily irrelevant, because it often informs what the story is about and how it goes, but all the best stories in any genre are about people, and that's what interests me, I suppose.

2/ What inspired you to write a folk-horror novel? Are you a big horror fan and if so can you name any pieces of horror art that have inspired you or influenced your love of horror?

Yes, I've always been a big horror fan, in both its written form and in visual media. I started off reading the likes of Stephen King, Shaun Hutson. James Herbert, far too young, and I love a wide range of horror at the moment. The genre is so diverse. There's out and out supernatural horror, and more subdued psychological stuff. And I have always loved horror comics. I absolutely adore the old DC anthologies like House of Mystery and The Witching Hour, and can't resist searching eBay for them. The likes of Swamp Thing and Hellblazer redefined horror in the 80s and 90s, and the horror comic is having a resurgence right now.

As to why I wrote a folk horror novel... I've always been fascinated with the sub-genre, ever since first seeing The Wicker Man. I like the idea that the supernatural elements can be subtle or even completely absent, and the fact that there's often a moral ambiguity about stories. There are rarely “baddies” or monsters in folk horror... just people who live differently. Granted, that often results in someone being horribly sacrificed, but, y'know...

3/ How does your journalism background help or hinder you when you write prose?

I think being a journalist means I can write pretty fast, and also it's probably helped me gain a better understanding of a wide and diverse range of people. You meet a lot of different people in journalism, often people you might not necessarily agree with or even like, but you have to put that to one side to find out what makes them tick. I see journalism and fiction writing as using different muscles... if you go to the gym (which, looking at me, you can tell I don't) you do different work-outs to exercise different muscle groups. Writing is like that. Journalism is writing, so is fiction writing and comic scripting, but they all seem to use different parts of the brain.

4/ Can you tell me a little about how you found the experience of writing comic-books?

I actually love the process of writing comic books. I taught myself looking at scripts online or in books, and I find it a really satisfying process. For me it starts with the story, like with any work of fiction. It has to follow the narrative rules, have a beginning, a middle and an end (even if its episodic) and have character development. Then I'll make handwritten notes on the story beats per issue or story, then I draw out a grid of however many pages the story is and make notes in little boxes of what happens on each page.

I like to visualise the entire comic book in my head when I'm writing, so I do fairly long panel descriptions. I'm probably too prescriptive, but I always make the point to whoever I'm collaborating with artistically that this is just my vision of it, and it can be mucked around with. The artist or artists always do a much better job than whatever's in my head anyway.

5/ If you didn't have to worry about trends, market demands, or budgets, what would you make next and why?

Well, I never thought I'd get to write folk horror, because that wasn't my "brand", so I've already ticked that box in one way. I think what I'd really like to do is a huge, sprawling epic comic featuring some of my favourite existing characters. I keep dreaming these things up. Now if only Marvel and DC would get back to me...

You might also enjoy

HERETICS

Set in 1999, HERETICS is a folk-horror story following the journey of investigative journalist Isobel Lockwood as she travels to a remote island off the coast of Scotland in an attempt to save her younger sister from the Children of the Sun, the free love cult founded by their father, which Isobel escaped from ten years earlier.

The most haunting thing I’ve read on the internet this week

“My foray into the online world of true crime fandom, where people treat school shooters and serial killers not as criminals but like characters from their favourite movies or novels”, an article for Tablet by Katherine Dee.

I have no idea how I found Katherine Dee’s Substack, but she writes insightfully about internet culture, which I usually interpret as meaning a writer documenting all the ways that unfettered access to the internet has broken us and ruined everything that was previously good about life.

One of the things in the article that has stayed with me is the notion that “When we’re teenagers, our feelings are so big and the reality of our lives are often so small in comparison. The violence of a school shooting gives teen angst the gravitas it feels like it deserves: It offers catharsis.”

The Columbine massacre felt like a moment when I was growing up where something changed and cracks appeared in the stability of reality. I spent a long time afterwards reading about it and thinking about it, including playing through Super Columbine Massacre RPG. The notion that school shootings are physical manifestations of an abundance of teen angst feels like it contains an element of truth that no analysis of a single school shooter could provide. This is something that I’m going to ruminate on for a long time, I think.

On Saturday night, all being well, I’m off to Shocktober Fest at Tulley’s Farm, which is billed as being Europe’s Largest Scream Park. This is the holy grail for Halloween in the UK, with 11 sets of scare mazes, Carnevil Cabaret and hopefully more horror than I can experience in a single night. I’ve wanted to visit for years and am convinced that something terrible will happen to stop me going. Wish me luck!

– P M Buchan