Happy New Year!

Where does the time go? It has been 12 weeks since my last email. If you’ve forgotten why you signed up, I’m P M Buchan, a transgressive writer who has written monthly columns and comic strips for Starburst and Scream: The Horror Magazine. I’ve collaborated with award-winning artists including John Pearson, Martin Simmonds and Ben Templesmith, and have been interviewed by Kerrang! and Rue Morgue. My work has been reviewed by Famous Monsters of Filmland, Fortean Times and Times Literary Supplement.

When I started writing IF YOU GO AWAY, each newsletter would include a quick-fire interview with a dark artist that I respected, covering everything from illustrators and graphic designers to authors and magazine editors. After the newsletter went on hiatus in 2021, I promised myself that when it returned, I’d try publishing longer-form interviews to see what sort of response they get. In the age of ten-second viral video clips, my hope is that someone other than me still values writing that you can get your teeth into.

Today’s newsletter mostly comprises an extended interview with Jason Atomic. Jason is an artist and occultist, co-founder of the Satanic Flea Market, creator of Satanic Mojo Comix, and a familiar face in subcultures across almost every continent. With a multidisciplinary practice informed by witchcraft and Satanism, Jason is an esoteric enigma who has exhibited in Tokyo, New York, Berlin and London. He is affiliated with the Art Model Collective, Battle Jacket Sewing Club and the Satanist Cartoonists, and also claims the unofficial world land/speed record for portraiture.

The first time I met Jason was at a comic convention in 2017. We were walking to a bar afterwards when he told me about the Satanic Flea Market. I asked him what else he did with his time, naively expecting to hear whatever boring way he paid the bills, and Jason shrugged and said, “Routine mischief”. This has set the tone for all of our interactions since.

I sat down with Jason at the end of 2022 to find out everything I could about one of the leading counterculture figures in England, in a conversation that touched upon censorship, Alexandrian Witchcraft, the founding of the Satanic Flea Market, weird fantasy and why not to name your events after obscene sex acts.

Jason Atomic, you are one of my favourite humans. What have you been working on recently?

Two notable new projects that I embarked upon in the past year were the Alex Sanders Lectures and the Mojozine.

In the 1960s Alex Sanders was an occultist and High Priest who founded and developed, with his wife Maxine Sanders, the tradition of Alexandrian Witchcraft. They were incredibly influential figures. Alex Sanders died in the late 1980s but Maxine is still around and she’s an inspiration. A few years ago I went to a lecture that she gave. Maxine had come out of retirement and was arguing that there are currently too many publicity-hungry witches active these days, kids on Facebook declaring themselves to be witches and showing off their workings for clicks on social media. Maxine argued that the craft is real and should be respected. Some things should be kept secret.

We hit it off with Maxine and started going to soirees at her house. I took some of the Satanic Temple guys around to meet her. In conversation, she mentioned how members of the Process Church used to come to their meetings. After that, we kept in touch. Maxine’s talks brought Alexandrian Witchcraft back into the public eye, generating renewed interest in the Alex Sanders Lectures, which were initially part of a Wiccan mail order course from the 1970s but have been out of print for decades, apart from in bootleg form.

When Maxine’s High Priestess started a publishing company, Rose Ankh Publishing, to get their books and writing back in print, Maxine asked if I would contribute. As a result, I was hired to illustrate The Alex Sanders Lectures with Commentary from Maxine Sanders.

What can you tell me about Mojozine?

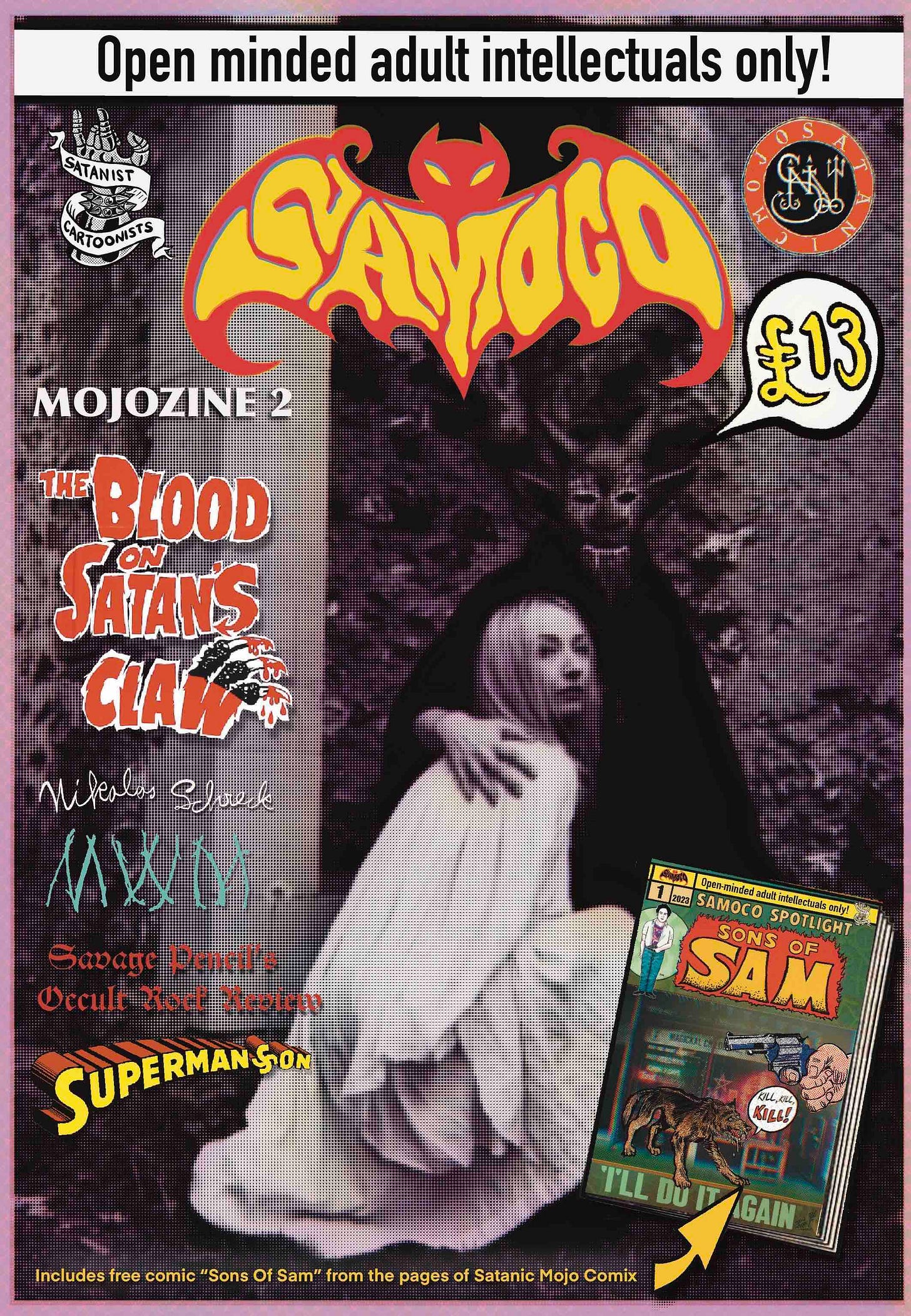

In 2022 I released the first issue of the Mojozine, a zine covering the first ten years of Satanic Mojo Comix (SaMoCo). The idea came about because we’d collected a lot of extraneous material that was really fun and I wanted to expand on what Satanic Mojo Comix was.

The first zine has a timeline of SaMoCo, an essay about its creation, features about different collaborators, plus essays by people including comic-book writer David Hine. It was exciting to reprint in colour things that we’d previously only published in black and white and to delve deeper into the ideas and philosophy behind SaMoCo.

Are there any other new comics on the horizon?

I can’t say for sure what’s next, but the most recent comic that I worked on was the SUPERMANSON Comixzine, which was made to tie in with the updated rerelease of Nikolas Schreck’s The Manson File: Myth and Reality of an Outlaw Shaman. The artist Savage Pencil once asked me if I knew of anyone who had ever created anything mashing up the names of Superman and Charles Manson into SUPERMANSON. So as we might, we couldn’t find any examples, so that became our inspiration, leading to a series of short strips contained in the pages of SaMoCo.

Nikolas Schreck recruited Manko Sebastian and I to create original collage illustrations for the UK release of The Manson File. When I heard that Schreck was putting out a final update of The Manson File, we decided to put the SUPERMANSON zine together, collecting our original comic strips alongside some new contributions by Nikolas, some of the collages that I collaborated with Manko on, and articles about some other obscure underground comics.

That’s something that I’ve learned about you in our conversations – more than just a comic creator or a fan of pulp entertainment, you’re a historian of counterculture comix.

It’s true that I’m passionate about trying to keep the counterculture and its history alive. The things I love have often been regarded as disposable, or not worth preserving, but to me it’s important to be able to follow a threat through society and say “I’m a part of that”. The counterculture is part of the thread of my tapestry, one of the things that has shaped me throughout my life, and underground comics are an important part of that.

Did you know that that EC Comics, one of the main targets of public criticism in the 1950s when Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, was originally called Educational Comics? The founder, Gaines senior, published these incredibly boring comics about the bible, but when he died in a bizarre boating article in 1947 his son inherited the company and changed the name to Entertaining Comics and the rest was history. Horror, crime, sci-fi… You can trace the lineage of underground and counterculture comics all the way from the pulp fiction of the 1920s and 1930s to the wave of censorship in the 1950s, then the backlash against it in the 1960s leading to more mean-spirited stuff in the 1970s, all the way up to where we are now.

It sounds like you’ve collected and studied counterculture comics for years. Do you have any plans to share what you’ve learned?

I really enjoyed working on the Mojozine, which helped me to document some of the creative process behind my own comics and place my work within the context of my contemporaries and the artists who influenced me. Putting the Mojozine together has helped me to see the importance of making information like that accessible and given me an opportunity to think about documenting other aspects of counterculture comics.

Cults are something that have interested me for a long time and I collect comic-books that were created by cults and fringe religious sects, often to use as recruitment tools. There are numerous links between comic-books and the Process Church of the Final Judgement. The Children of God created comics in an attempt to normalise some seriously questionable things. And Aum Shinrikyo, the Japanese doomsday cult behind the Tokyo Sarin attack, also produced their own comics. They actually had their own gift shop, which stayed open for a month after the attacks. I managed to get a store loyalty card before it was shut down. None of these comics are widely available now and although you can find piecemeal information online, I want to make it more accessible and ensure that it doesn’t get forgotten.

As a creator, what sort of reception do your comix get among mainstream comic-book readers?

When I’m creating things like the Mojozine or SaMoCo, I know that most traditional comic-book stores won’t stock them, so it’s difficult to reach readers through that route. If you’re already a famous, established comic creator then you can make art filled with as much explicit sex and violence as you like, but stores are a lot more conservative about selling something independent like Satanic Mojo Comix. It doesn’t matter that we get some amazing contributors, people like Krent Able, Savage Pencil or Garry Leach, there seems to be a preconceived notion of what independent comics in the UK should be, and we aren’t it.

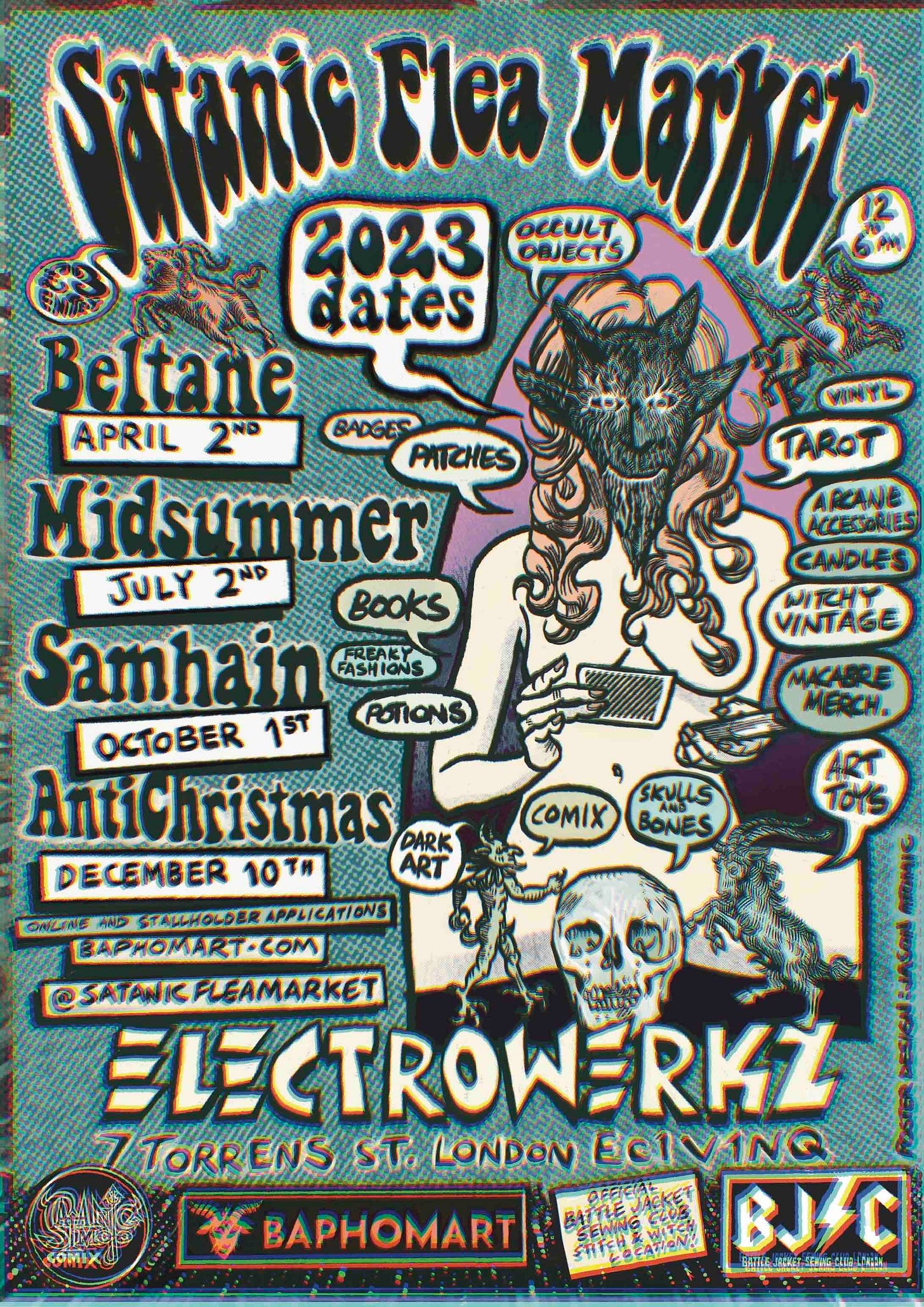

Rather than limiting our audience to mainstream comic-book readers, I’d say that Satanic Mojo Comix sells to members of the general public. Not everyone, but there are enough of us. The truth is that I don’t really fit in anywhere and I never did, so I created my own scene. We set up the Satanic Flea Market to promote the release of the third issue of SaMoCo and ever since the first event, that has kept us ticking over nicely. With the number of visitors that we consistently get, we don’t need mainstream distribution.

Tell me more about the Satanic Flea Market. Where did the idea come from?

Back in 2015 when I was working on the third issue of Satanic Mojo Comix, I wanted to curate an exhibition and invite the different artists we’d been collaborating with to contribute artwork themed around witchcraft and Satan.

I’d seen work by the art collective Guerrilla Zoo, whose shows had included one called Modern Panic and one I loved that was a celebration of 100 years of William Burroughs. It was clear to me that their strengths were in areas that lay beyond my means, but also that some of their weaknesses were my strengths. So I got in touch and proposed a teamup.

The founder of Guerrilla Zoo, James Elphick, was well up for it. So we worked on that first event together and billed it as Come To The Sabbat, a Festival of Dark Arts, which was mostly based around Satanic Mojo and the people who had contributed to it. We had a black-light room, with giant black-light paintings, and a room based on the lives of heavy metal fans during the Satanic Panic era, including old black-and-white televisions and a record player.

How did Come To The Sabbat lead into the Satanic Flea Market?

After accumulating a lot of occult memorabilia and moving around a lot, there came a time when my parents got tired of me storing my stuff in their garage, which coincided with Come To The Sabbat. There was a lot to get rid of, so we turned the last day of the festival into a Satanic Flea Market, where I was going to sell all of my old records and comics. I asked if any other artists wanted to do similarly and then word got out. Henry Scragg, a dealer in the macabre who runs Curiosities from the 5th Corner and specialises in taxidermy and bones, was one of the people who responded. We had six or seven hundred people turn up, queuing around the block. It was such a success that we threw another Satanic Flea Market at Christmas, when 1,200 people attended, and they’ve been quarterly events ever since.

We’ve had to move around a lot, to keep the Flea Market going. One of our venues got greedy and started wanting a cut of the dealers’ profits, but we were at a point where 2,000 people were spending money at the bar all day long. Surely that should have been enough for them! There were so many people buying drinks that some venues didn’t want to host us again because they found it too much hard work to keep the bars running.

Since then we’ve been at Electrowerkz, home of Slimelight. I like that Electrowerkz grew out of the squat scene. I was there when they first squatted that building. There aren’t many alternative venues around anymore, so I could see that being our home for the foreseeable future. I love hosting the Satanic Flea Market. Every time, people come up to me and tell them how much they enjoyed it. There’s a community that shows up and that’s what I want to do, to nurture and grow a community of people who support each other and make the world a more bearable place to live in.

You’ve led a fascinating life. Can I ask how your different mix of experiences led you here, now, juggling so many different endeavours?

I feel like we’re in a good place with the Satanic Flea Market and SaMoCo, we’re in a period of growth. But it wasn’t always this way. For a long time, it felt like my career was out of sync with the world and every five years I’d jack everything in and start something different.

When I was young, I became obsessed with Japan and Japanese culture. I wanted to find out everything I could about Japanese myths and legends. Of course, because of my love of comic-books I had a huge interest in manga, but more than that, I wanted to collect everything related to Japanese pop culture. If I saw an imported toy with big eyes, I’d grab it there and then, just as I’d buy Japanese books and pore over them, studying the pictures and trying to teach myself to read.

I moved to Japan in the 1990s and as soon as I was surrounded by easily accessible Japanese toys there was no longer any point in collecting them, because I was surrounded by them every day. Once that thrill of the chase was gone, the connection was broken and my real life became more interesting. I took walks in the woods, learned how to cook, took an interest in being alive. That time in Japan really saved me.

The problem with my time in Japan, however, was that when I returned to London it felt like I was perpetually one step ahead of the curve, launching ventures that people weren’t ready for yet. I’d spent five years honing my life-drawing skills overseas, which when you team that with Japan’s love of cosplay became really exciting and different. We tried to combine the two things in England, but at that point nobody knew what cosplay was yet and so nobody got it.

Similarly, I started working with my punk brother Johnny Deluxe and the nomadic nightclub event Freaktastic! was created to showcase performances of our electronic punk band, Fist Fuck Deluxe. The concept of the show was that we were ancient demons who had tyrannised the land but had been projected forward in time by a coven of sorcerers and trapped inside a pop group. The genius of this plan being that the demons relied on fear for their power, but regardless of how wildly they behaved, in the context of being a pop group they would be loved and adored regardless of how outrageously they acted, thus rendering them impotent.

I thought that we’d keep the counterculture alive and combine art and music in a way that couldn’t be appropriated by the mainstream or commercialised. In a way, it worked. The people who attended loved it, but nobody wanted to write about something called Fist Fuck Deluxe, so there was a limit on how far we could get. I couldn’t help making things difficult for myself. Whenever I see the formula for someone else’s success I don’t want to do it.

For a while I seriously thought about trying to get back into fine art, which was something that I’d been connected to in the past, but by that point everything seemed to be Banksy-inspired urban art bollocks and there was no room for someone like me. Finally, when I had the idea for Satanic Mojo Comix, I dedicated myself to something that was wholly my own thing, and that was when things started to take off. The best advice I can give to any artists who are struggling is to do your own thing. Trying to be a part of someone else’s trend will never work.

Going against the grain of a lot of modern artists in the UK, you’re very dedicated to freedom of thought. Was this always the case, or have there been any events in your life that led you in this direction?

One memory that stands out for me happened when I was a teenager. I had too much time on my hands during one of the summer holidays, so I set about decorating my school history book with what I thought were appropriate decorations for a history book. I’d been looking at a lot of World War 2 propaganda that year, so I drew a leering grim reaper wearing a swastika armband and drooling blood, which I thought was a pretty mundane example of wartime propaganda art. Well when I got back to school, I got called out of assembly one morning by the Assistant Headmaster. It turned out that my history teacher felt “too disturbed” to face me in person. The Assistant Headmaster had a lot to say about what I’d drawn, including that it was the sort of filth he’d expect to find in the back alleys of Soho.

Finding out that adults could be scared of children was a revelation. As was what I took as his instructional advice to visit Soho and seek out its seediest corners. When you’re a child, adults want you to just follow the rules and keep your head down, to consume the same things as everyone else. But when we start thinking for ourselves, the system that they designed to pen us in starts to come crashing down. It’s ridiculous really, grown-ups losing their shit because they don’t remember what it was like to be children. In a way, that led me to Satanism, which to me really just means thinking for yourself, taking responsibility for your own actions, not following orders and not trying to blame someone else if you mess up.

When you talk about thinking for yourself, I’m struck by the fact that your comics are filled with lurid sex and violence, but that you give more thought to morality and your own beliefs than artists who make much tamer work. Where do you draw the line when it comes to what you’ll publish in Satanic Mojo Comix?

Because it doesn’t only include my own work, I always say to contributors that there are no restrictions on theme for SaMoCo and there’s no censorship, but I don’t want to publish anything that’s punching down. Work that I publish, I like to be justifiable, so we steer clear of racism, rape, anything that persecutes someone who is already persecuted.

There are a lot of examples in the UK of mainstream entertainment that achieves popularity but does so by appealing to the worst in people. Little Britain is the sort of comedy I’d have watched on TV with my Mum when it was on. It was a funny show, until you stop and think about it. When you do, you realise that it’s basically a series of comedy sketches based on bullying and ridiculing people for being poor or uninformed. It’s not cool.

A lot of people won’t ever think about it. They’ll laugh at the stupid commoners and not realise they’ve done anything wrong until you point it out the them. That’s not the sort of world I want to live in. There’s a lot that’s rotten in pop culture, too many victims created to justify narrative progression. Well I don’t want to glorify turning people into victims. Mad Max was a great film, but it all hinges on the rape and murder of his wife. Don’t we have any other tools at our disposal to show that a character is a good guy? When I watch a mainstream crime television show and the focus of our entertainment is on the cops and the criminals but not the prostitute who gets raped and murdered, I find that more offensive and dehumanising than anything I’d want to create in my own art or publish by other people.

We live in a complex world and we have to be prepared to see shades of grey, in between good and bad. Everyone wants to wear what Anton LaVey used to call the good guy badge, but it isn’t helpful. It’s difficult and upsetting to acknowledge the complexity of a human, it’s easier to deny that complexity. The truth is that a lot of people object to the notion that they’re being asked to put the work in and come to their own conclusions. People want everything to be spoon fed to them.

I’m personally drawn to the intersection between Satanism and horror. Are you a big horror fan?

I’d say that I actively enjoy horror films. I love stories and films by Stephen King and Clive Barker’s Books of Blood. I do tend to prefer older stuff, Gothic horror, Dracula, Lovecraft, the weird fiction end of things. More than that, I’m really into Weird Tales and those old pulp magazines. I feel like there was a period when genre wasn’t so rigidly defined, when horror could bleed into poetry, dreamscapes, historical stories, detective stories, drugs…

The early 1900s were such a fertile growth period, with weird fantasy leading into the creating of EC comics, all of that gore and the fear of juvenile delinquency and the creation of the Comics Code. Weird Tales typifies an art form that could be quite adult but had a decadence and creativity to it. Plus any of that weird fantasy meets my interest in lucid dreaming nicely, the two go hand in hand.

Finally, I’ve wondered for years, are you a part of any organised Church of Satan?

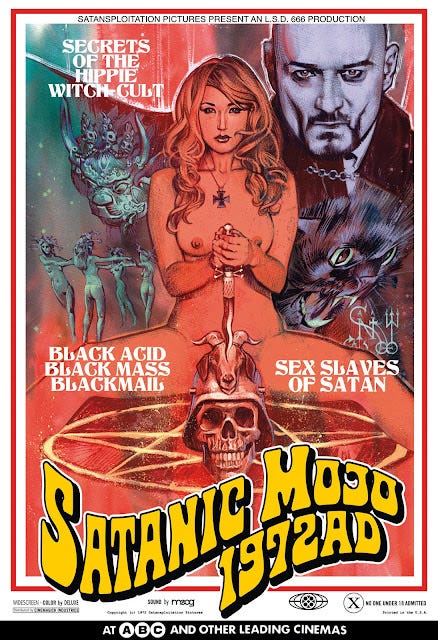

I’m not a member of any organisation, no cults and no churches. When I created Satanic Mojo, it was an anagram of my name, but I chose it because I felt the zeitgeist of culture leaning in that direction, leading me.

There’s so much conflict in the world, even the Church of Satan and the Satanic Temple are at each other’s throats, but I’ve always felt accepted. Whatever school of Satanic thought you choose to follow, we all have our basic core beliefs in common.

I believe that every child is born a Satanist, whether they know it or not. I have to choose what I believe is right and what I believe is wrong, then act accordingly. We each make our own way in the world and this is my way.

Across seven issues of Satanic Mojo Comix, numerous inserts, t-shirts, sticker packs, live events, fashion collaborations and who knows how many other spin-offs and extensions of the concept, Jason Atomic has created something that is unique for this century in the UK. By combining incredibly accomplished fine art, painting and illustration with stark examples of obscene outsider art and transgressive filth, all filtered through a cocktail of reminiscences of the most extreme highs and lows of the counterculture in Western society throughout the 1900s, the end result is an assault on the senses and so much more than the sum of its parts.

What you take away from a reading of Satanic Mojo Comix will depend on what you bring to the table in terms of an appreciation of the history of independent comics, pulp fiction, the occult, mind-altering drugs, Satanism or transgressive art. It’s possible to pick up an issue and gawp at the late Garry Leach’s polished illustrations of Casper the Ghost getting too friendly with a number of enthusiastic partners, laughing at the brilliantly smutty parody, without also realising that Garry was one of the UK’s most influential comic-book creators. However, understanding the calibre of contributors that Jason gathers together helps to demonstrate the anarchic undercurrent that used to underpin so many comix in the UK, an absence of virtue that’s getting forgotten in the drive to commercialise every modern art form.

Satanic Mojo Comix provides a home for the kind of artists whose subversive talents are no longer in high demand by a medium that becomes more sanitised with every year that passes. It’s ironic that in the 2020s (in the UK at least) we’re probably more relaxed about bad language, anti-religious sentiment, graphic sex and violence than at any point in the past hundred years, but in lieu of government-sponsored censorship bodies we’re in thrall to social censure to such an extent that most artists self-censor before reaching the act of creation.

If you want to see truly transgressive art, I’d recommend Satanic Mojo Comix. For every pitch-perfect Disney parody in one issue, the next you’ll find the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles having graphic sex with the face of a dead body for no discernible reason. Clever deconstructions of the demonisation of free-spirited hippies are juxtaposed with literal pornographic images from Satanic sex rites. These aren’t comic strips designed to be adapted for film or television and these aren’t concepts that demand to be adopted by the mainstream or to be added to the school curriculum, they’re a celebration of the medium of underground comix, aimed at open-minded adults.

Satanic Mojo Comix are dense throwbacks to the period before decompressed storytelling throttled the pace of the mainstream American comic-book industry and before Brian Michael Bendis convinced a generation of writers that a group of superheroes out-of-costume and arguing in a coffee shop was enough action to fill an issue. The pace and layout of Satanic Mojo Comix varies from artist to artist, but cumulatively a house style becomes apparent, packing every panel and page with extraneous, grotesque details, enough to reward repeated re-readings. I wouldn’t recommend reading all of the issues back-to-back, because after a while you become desensitised to the material, but if you pace yourself, you’ll find these a great antidote to so much else that’s safe and friendly.

And of course, underpinning everything are the illustrations, comic strips and artistic stylings of Jason Atomic, whose growth and development you can follow from the raw, unpolished filth of the first issue to something altogether sharper and more refined by issue seven. His love letter to the comics that he reveres reads like Jack Kirby had been forced to drop acid and stay awake for a week drawing the mad ramblings of a sex-starved Satanist in his final days on death row. The power of Jason’s vision is such that he more than holds his own, despite frequently sharing space with some of the most effective dark visual artists on the planet.

Given the subject matter of this newsletter, I can’t help but reshare one of my favourite playlists, Satan’s songs, which is basically a collection of bad music for bad people, including Amigo the Devil, Jill Tracy, Twin Temple, the Bridge City Sinners, Alkaline Trio, Danzig and more:

That’s all I have time for today. Thanks to flu I had to write off most of December and January, leaving me weeks behind where I wanted to be with edits on my novel. I received some great advice about a couple of apps that are helping me to pick up a lot of schoolboy errors in my prose during the arduous editing process. However, this week a very good friend with a much more accomplished track record than mine also pointed out some gaping omissions in the novel as it stands. As a result, I’m going to swallow my desire for it to be finished and sit down again to expand what I’ve written and give some of the characters more room to breathe. If I could pay to have my wisdom teeth removed instead I would, but I have to work on the basis that this could be the only novel I ever publish, so I need to put the hours in to fix what’s missing.

If you enjoyed this edition of IF YOU GO AWAY, please tell the world! Share it with a friend, or let me know in the comments or by email. There’s an exponential difference in effort between emailing five quick questions to an artist and grilling them for hours then turning that conversation into a satisfying interview, so I’d love to hear if you thought it was worth the extra time spent.

Best wishes,

P M Buchan