Meet author Cy Dethan

"I like to play on the narratological intersection where Fucking Around meets Finding Out."

This week on IF YOU GO AWAY it’s all about Cy Dethan and his debut novel, Bad Sector. I met Cy through the UK comic-book scene over a decade ago, so after the interview I give a rundown of what things looked like for independent comic creators in England when we met and how Cy has blazed his own trail in the years since.

I’m P M Buchan, a former comic-book writer and lover of horror and dark art. I’ve written monthly columns and comic strips for Starburst and SCREAM: The Horror Magazine. I’ve collaborated with award-winning artists including John Pearson, Martin Simmonds and Ben Templesmith, and have been interviewed by Kerrang! and Rue Morgue. My work has been reviewed by Famous Monsters of Filmland, Fortean Times and Times Literary Supplement. I’ve collaborated with bands including Megadeth and Harley Poe, written for clients including Lionsgate and Heavy Metal Magazine, and my first serious comic was rejected by three printers on the grounds of obscenity before we found someone willing to risk on printing it.

An interview with Cy Dethan

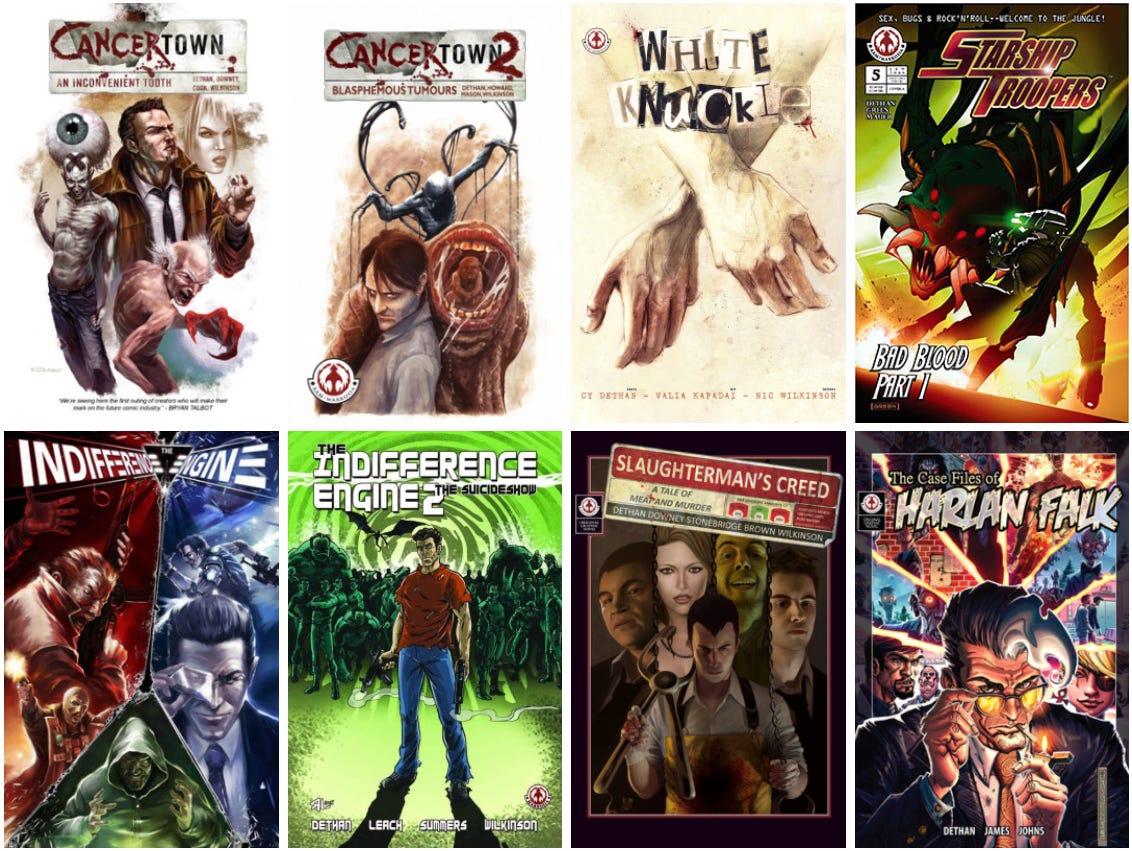

Cy Dethan is a British comic-book writer who made his industry debut in 2006 with Starship Troopers: Extinction Protocol, before going on to write the ongoing series. Over the years, he has carved out a space in British comics with a string of dark, genre-spanning graphic novels, including Cancertown: An Inconvenient Tooth, Slaughterman’s Creed, The Indifference Engine, and White Knuckle, working alongside artists like Stephen Downey, Rob Carey, and Valia Kapadai. His work often blends psychological horror, crime, and speculative fiction, pushing the boundaries of independent British comics. In 2025, he made the leap to prose with his debut novel, Bad Sector, a dystopian noir thriller about an executioner navigating a sentient city.

A longtime creative partnership, Cy’s work is often brought to life with the lettering, editing, and storytelling instincts of Nic Wilkinson. Nic’s has played in integral part in Cy’s most acclaimed projects, working together for the past 20 years on collaborations that are as sharp in design as they are in narrative weight. Together, they have produced some of the most distinctive and uncompromising independent comics in the UK.

In this interview, Cy discusses how his background in professional magic influences his approach to storytelling, why he instinctively resists genre conventions, and how his work explores the blurred boundaries between crime and horror fiction.

You were once a professional magician before moving into comics and now novels. Do you see any connections between the art of illusion and the craft of storytelling?

Yeah, absolutely. There's a lot of storytelling-adjacent work that goes into most forms of magic. In performance, you're generally running two separate scripts at once - one out loud for the spectators and another silent one in your head. The silent one's critical since it's where you play out your own reactions to the magic as it happens, as if you were experiencing it for real. Beyond that, there are principles of timing, deception and misdirection that are equally applicable in magic and fiction. Bad Sector's a decent example of this. It's essentially a crime mystery, which requires a certain amount of narrative sleight-of-hand in the first place. On top of that, I'm using what a magician would call the one-ahead principle and time misdirection to pull off some of the story's biggest moves.

Your stories have spanned everything from cyberpunk dystopias and serial killers to samurai splatterpunk, often pushing against genre conventions. Do you set out to break the rules, or do you find that your stories naturally resist neat classification?

I guess I wouldn't call it a conscious choice, but developing a story is like having a protracted argument with yourself - and sometimes you have to break a couple of the rules of engagement to win. Regardless of medium, advice books on writing and genre expectations usually read like pure poison to me. Not all of them, to be fair, but you too often see established writers laying down their pet peeve lists like they were inviolable laws of nature. If I cross a few meaningless lines to land a particular plot beat or build the kind of story I want to tell, then I don't stress out about it.

Pretty much all works of art that I've ever found genuinely meaningful have been acts of vandalism of one sort or another, conceptually or literally. Comics in particular have always represented kind of a punk medium to me, so they lend themselves to experimentation and subversion. If there's a formula, I instinctively want to pull it apart to see how it works. If there are conventions, I want to stress-test them - and I've learned that pissing off the right people is ninety percent of the job.

Your work regularly treads the line between horror and crime fiction, from the grotesque body horror of Cancertown to the brutal underworld of Slaughterman’s Creed. What do you think connects these two genres and what draws you to that space between them?

You might say I have a healthy respect for creative transgression, which is where horror, crime and even comedy all grind up against each other. I like to play on the narratological intersection where Fucking Around meets Finding Out. I don't know that I've ever set out consciously to write an authentic 'horror' or 'crime' story, but I guess a lot of my work tends to metastasise in those directions. It's virtually always a character that starts the process for me, though, and in getting to know that character I start to understand the situation they're in and the pressures they're under. The story spins out of that discussion.

The moment you start thinking in terms of strict genres, though, I think you're at risk of slamming doors you should be crowbarring open. Those comfortable conventions will kill you.

Which writers or storytellers had the biggest impact on your approach to narrative? Are there particular works of art that shaped the way you think about writing?

I think the biggest influence other writers have had on me is in making me want to write in the first place, rather than determining the way I actually do it. In prose, I was a big Douglas Adams reader as a kid, and William Gibson a little later. I'd be hard pushed to find their fingerprints on anything I've written, but I'm too close to my work to make any real judgements about that. As a comics reader, I hit that perfect era when giants like Bryan Talbot, Frank Miller and Alan Moore were changing the game for everyone, which in turn steered me toward emerging powerhouses like Grant Morrison and Garth Ennis. Again, though, I couldn't join any specific dots between their work and mine.

Looking (at least partially) outside of fiction, I guess I could point to Mark Brandon 'Chopper' Read's various pseudo-biographies as influences of sorts. Beyond that, I'd just be listing magic books, paranormal debunkers or 80s public information films about kids drinking industrial chemicals and getting churned into mince by farming equipment. Oh - and Gunther von Hagens' Body Worlds, which took vandalism of the human form to some utterly breathtaking places.

You and Nic were some of the first people I met creating comics in the UK and I know you have a partnership that's both personal and creative. Have you created art together since you met or did that come later? Has your approach to collaboration evolved over time and do you each have distinct creative roles, or is it a more fluid process?

We started out making things together almost immediately. While we were still at university, Nic was already drawing character designs for me. One of the first I remember was her take on a character who would eventually become Crosshair from Cancertown. We worked together on my first professional comics work, and on virtually everything I've done since.

Most of what I know about working with an artist, from giving your co-creators breathing space to managing workflow and deadlines, I learned first from Nic. These days, in addition to lettering my comics, she regularly makes encaustic wax paintings based on things I'm writing - including a set from Bad Sector that I absolutely love. I also run a lot of tabletop RPGs - which is a legitimate form of collaborative storytelling in its own right, and one that really sharpens your writing weapons. Nic will sometimes take moments from our games as inspiration for her own art.

How does Nic's lettering and design shape the final tone and impact of your stories? Are you ever torn in different directions creatively and are there moments where her lettering choices have changed the way you saw a scene?

I feel like we're always in sync, creatively, having basically learned our crafts together. I think the most important lesson I get from working with Nic is to trust my co-creators to shoulder their share of the narrative load. Nothing kills a comic faster than a writer who needs to hear their own voice in every panel. Nic approaches lettering from the perspective of an artist, and that goes way beyond font choices and balloon placement. She has this way of turning the lettering into functional artwork, and weaving it into the panel composition in ways that, honestly, I've never seen anywhere else. The major boost we get from that is the ability to do more storytelling with fewer words on the page, and that's an incredibly valuable thing in comics.

Do you approach writing differently depending on the format, alternating between comics and prose? Do you have a daily creative process, or is it more chaotic

Writing my first long-form novel has been an opportunity to shake up my whole approach and workflow, but the basics of story construction haven't changed much for me. I still work from the characters outward, building the story around their attributes, drives and limitations. After that, though, it's a whole new world. In comics, I can plan entire stories out page by page before I ever start the actual scripting process. That way, by the end of day one, I've already got all the bones of the story in place. I then do a pass where I break each page down into panel beats, followed by a dialogue pass and then a final run-though to flesh out the panel descriptions.

For Bad Sector, all of that had to change. I had a structure in mind that featured multiple timelines set years apart, with an alternating format that still required the two separate stories to sync up and inform one another. It's a much bigger story with a more ambitious structure than anything I'd tried before, and I had to change my whole process around it. In comics, I'd got comfortable holding an entire story in my head at once so I wouldn't suddenly find myself stuck with a question I couldn't answer or a problem I couldn't solve. With Bad Sector, sheer logistics made that a much bigger challenge. I was dealing with more characters, some of whom existed in both timelines at different points in their personal development. I was launching multiple story and character arcs that all needed to land at specific moments - and every so often the world would do that charmingly helpful thing it always does by throwing up a real-world situation or scientific discovery that so completely encapsulates what I'm struggling to write that I have to sledgehammer out something load-bearing from the story to accommodate it. So yeah - the shift into long-form prose was a chaotic one at times, but in the end it led to me developing a whole new routine just to keep on top of it.

One thing that did feed through directly from comics to prose was the narration. In comics, we're all very comfortable with the idea of a first-person narrator speaking in the present tense. It's one of the most basic storytelling modes we have, and we don't question it. Right from the outset, for both structural and character reasons, I knew I needed to tell Bad Sector that way. It's not something I've seen a lot in prose, so it felt like the right kind of risk to be taking. More than that, though, it was key to portraying the book's main character, who by necessity experiences his life only as a constantly evolving moment. No past to mourn, no future to fear.

As a writer, are there particular themes or ideas you find yourself returning to again and again? What obsessions fuel your work?

Yeah, inevitably. I'm constantly drawn to characters who are in conflict with their own identities. Outsiders who are strangers to themselves. People living and dying in the shadows of their own egos and alter-egos. I like unreliable narrators and outcasts. Cancertown's Vince Morley is, in his own mind, a literal dead man walking. Seth Rigal from White Knuckle is a former serial killer whose one moment of clarity destroyed his entire sense of self. In magic we're talking about people like Houdini and William Robinson, who literally lost their lives to the fictions they'd made of themselves. In literature, it's Tyler Durden and Dorian Gray.

Many of your stories deal with transformation, whether that's physical, psychological, or more existential. What is it about the idea of change (or its impossibility) that fascinates you?

Okay, that's kind of an essay question, but I'll try to sum it up without exceeding my wild tangent quota for the month. I like stories that catch unstable or alienated people at pivotal moments. There's a point in every magic trick where the spectator realises that a very secure assumption made in their recent or distant past is at odds with their reality in the moment. The coin really isn't in my hand. In fact it was probably never in my hand and now it's too late to work out where it went. That folded playing card that's been sitting clearly visible under a glass on the table for the last five minutes really is the one you only just chose from the deck and signed thirty seconds ago. That transitional moment where the whole world shifts around you is the key to my whole approach to storytelling. The sense that not only is reality different from the way you'd understood it, but that - critically - it has necessarily always been this way, and the only thing that's actually changed is you. That's the position I strive to put my characters in - and, to whatever extent I can, I want to offer the exact same moment to a reader.

If time, money, and market concerns weren’t an issue, what would you create and why?

It's an interesting question. There's really only one basic rule that guides my writing, and it's an easy one to follow. I won't write a story that I wouldn't want to read - and so far I've never needed to. To that extent, money and markets have never felt like pressing issues to me. I'm a professional writer in other contexts, and that's where my living comes from, but my fiction work is kept separate from those concerns. There are certainly writers who make fantastic careers for themselves without violating Cy's Law, and if I ever found myself in that happy position then I'd hardly complain about it. So far, though, I've been free to write every story I ever wanted to with a clear conscience.

That said, I have a fucking amazing crime comedy screenplay in the chamber right now if I ever find myself stuck in a lift with Christian Slater and at least one Coen brother.

Read a free preview of Cy Dethan’s Bad Sector and order here.

Let’s end at the beginning: How I met Cy Dethan and Nic Wilkinson

I met Cy Dethan and his partner in crime, Nic Wilkinson, sometime around 2010 or 2011. Around that period I was running graphic novel reading groups for teenagers at a public library in Greater Manchester, and after some successful fundraising, we hired artist Emma Vieceli to come in and run comic creating workshops with the group. I knew Emma by reputation, from her work with indie UK manga studio Sweatdrop, but we hadn’t spoken in person.

She travelled up to Manchester for the event, and towards the end, when we were chatting, she persuaded me to join Twitter. It was amazing, she said, like texting your friends but people all over the world could join in, and she used it to catch up with other comic creators and meet up when she was in another city. I was completely convinced, signed up that day, and used it to begin networking with other aspiring comic creators, essentially meeting the writers and artists who I’d come to consider to be peers.

Finding my people

Through Twitter, I came across Cy and Nic and arranged to meet up with them the next time I was at a comic convention. This was easily over a decade ago, but I remember clearly that all the pros had a private room to have dinner on the Friday night before the convention, and the rest of us met up in an adjacent bar. Meeting Cy and Nic for the first time was like meeting old friends. There were a lot of politics in UK comics (which haven’t exactly shrunk since then…) and a lot of bullshit posturing. This was the period when it felt distinctly like genre comics were looked down upon by a cool crowd of indie diary-comic posers.

The 2000s: A directionless decade for UK comics

The 2000s felt like a directionless decade for UK independent comics, outside of small press and fanzine scenes like FutureQuake, which helped launch the careers of a few notable new talents. In terms of mainstream UK comics, there was little growth, and few new launches from major publishers.

At the same time, manga flooded UK bookshelves, but British publishers were slow to react, with the exception of SelfMadeHero, which launched its Manga Shakespeare line, and Tokyopop UK, which ran Rising Stars of Manga, opening doors for UK manga-influenced creators. The only notable indie manga exception of the 2000s Sweatdrop, Studios, which provided a launchpad for many artists who were later picked up by SelfMadeHero and other publishers.

No love for genre comics

At conventions, ignoring the new readers that manga brought in, you could feel the cultural divide between old and new. Indie diary comics were in, while any genre comics (apart from the evergreen 2000AD crowd) were seen as relics of the past.

By the late 2000s, the closest thing to a new indie movement came from British creators emulating the diary comics popularised by Jeffrey Brown and books like Every Girl Is The End of The World For Me. The peak of this scene came in 2012, when Adam Cadwell (The Everyday) and Marc Ellerby (Ellerbisms) launched Great Beast, an imprint designed to take their work to a mass audience.

For a while, emo music and diary comics defined UK indie comics. Pretty boys in skinny jeans were making comics about breaking up with their girlfriends and how badly their feelings were hurt, and everyone loved it. A few short years later the winds of change would arrive and by 2020 the underground of UK comics would be almost unrecognisably changed, but back in 2011, all we knew was that genre comics were out, and heartfelt diary comics were the future.

“The moment you start thinking in terms of strict genres, I think you're at risk of slamming doors you should be crowbarring open. Those comfortable conventions will kill you. “

– Cy Dethan

Creating comics without compromise

That was the vibe when I met Cy and Nic, and they unapologetically did not give a fuck. Between the two of them, their interests ranged from magic and escape artists to epic fantasy and medieval poetry. I can’t think of anything less likely than either one of them sitting down to willingly read a diary comic about someone’s feelings after a breakup.

Cy and Nic are a couple of inspiring artists who create the kind of stories that they enjoy reading, following their muses with disregard for wider trends or what anybody else is doing. They’re supportive of their peers, collaborating with emerging artists before they hit the big time and mentoring less experienced artists when they have something to share. They’re as likely to contribute to shared universes or lend their names to anthology Kickstarters as they are to focus on their own stories. And they’re incredibly prolific, with countless completed graphic novels to their names.

A career-long creative relationship

In the years since we’ve met, I’ve tried to amplify Cy and Nic’s work whenever I had an opportunity. Going back through my archives of previous publications, I’ve written about their comics for Bleeding Cool, SCREAM, Starburst, and even INFINITY, a magazine by Panel Nine that focused on iPad and digital comics.

They were never afraid to return the favour. I’ve had countless quotes from Cy endorsing different projects that I’ve worked on. They were both present at my HERETICS launch exhibition in 2016. In many ways, my writing career has run parallel to Cy’s for a number of years, and while I’m querying my new novel with agents, Cy has beaten me to it and published his first prose novel, Bad Sector. If ever there was a creative team in the UK who deserved success and wider acclaim, it was Cy Dethan and Nic Wilkinson.

You might also enjoy

The Three Coffins

The Three Coffins is a love story for hopeless alcoholics who can’t find a way to change. When a lost soul is given a second chance in the underworld, he discovers that even in death, temptation is impossible to resist.